Our towns and cities grow and populate in several different ways and this creates several different patterns. Urban planning largely dictates how the modern city is formed, usually in grid like, linear patterns of straight lines and creating wide open spaces, prioritising clear vision for direction, with streets acting like a spine to guiding to your destination. But it isn’t always like this, on both an urban and architectural scale, some urban spaces have grown organically as time passes, naturally creating communities that grow in a sporadic format. And despite their differences, there is still debate over what creates the best style of living.

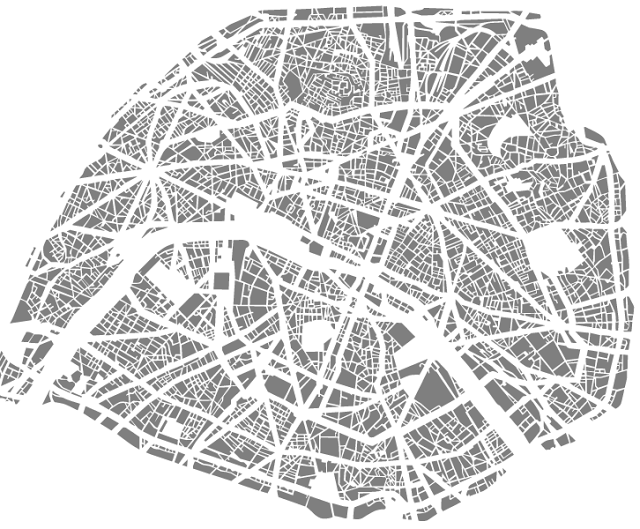

Urban planning is nothing new. For as long as we have been building, we have set out to organise the way we do so, creating many different patterns and modular ways of designing peoples relationships with space, many hearkening back to nature and the body for inspiration. For the Romans, it was designing straight roads on a grid, which is still used in many of the world biggest hub cities, New York, Barcelona, Paris and Glasgow to name a few. Barcelona famously contrasts organically laid out areas such as the Gothic quarter with the Eixample quarter which is distinct for its wide roads, and open spaces, a godsend for vehicles and pedestrians alike but failing to create the same atmosphere and culture as Barcelona’s distinctly Catalan streets throughout the Gothic quarter. Paris was also famously bulldozed and redesigned after the carnage facilitated by Paris’ narrow and winding streets. Pathways were blocked by rebels during the revolution, making walls out of any material at their disposal. These were replaced by wide and open boulevards and avenues making up blocks (with smaller streets in between) to stop parts of the city from being separated again, and therefore stopping the people from another uprising and taking control of their city. Glasgow’s high street and town centre was riddled with disease and poverty during the 18th century, as a response to this, the city was redesigned west of the high street in three separate developments. This allowed the city to grow into what became the more affluent west end of the city and marked the start of Victorian Glasgow, the second city of the empire and a city powered by engineering, invention and investment.

In contrast to this, many cities in Latin America have given birth to communities which we know as favela’s. These are communities that have arisen out of a demand for housing in densely populated cities where people require being close to the city, without commuting large distances and all for a low price. In favela’s people tend to build their own infrastructure over time, and as they require it meaning the plan grows more organically, with street with size fluctuating, similar to how veins flow into capillaries, and streams flowing into rivers. This, unlike many of our cities, has not been predetermined but still facilitates life. In Rio de Janeiro, the occupants are called “people of the hill” because of the way the community has grown up and over the hill, with many structures stacked on top of one another. This is a place that is home to both vicious drug gangs, and creative resourceful pioneers, both of which only existing in this community due to the governments lack of control here.

Some may argue that these organically formed hubs, are only a cause for concern, giving drugs and crime a home and power over people causing dysfunction. That pacification (the government coming in and driving out gangs, usually in a very violent and unsuccessful operation) needs to happen for people to live happily within the community. But the same community also creates a hub for vibrant members of the public to take control of their own space, challenging social issues, usually with inspiring outcomes. Many Brazilian cultural staples such as samba and carnival have roots in the favela, and to stand against the favela would be to stand against creative and political freedom.

I feel that there is both pros and cons in both predetermined and naturally occurring urban spaces, but what they really stand for is control over people and the city. Urban planning creates an opportunity for safer public spaces, but at what cost is this to peoples instinctual cultural development and is there a way to design our towns and cities while still giving power to the people?